Gilbert (Gustav) Rohde (1894-1944)

Gilbert Rohde

Gilbert Rohde was born in the Bronx, the son of a cabinetmaker. He graduated from Stuyvesant High School, a school which was restricted to gifted students, being known at that time for its rigorous vocational studies program. A third of the Stuyvesant studies were devoted to shop classes which included freehand and mechanical drawing, cabinetmaking, joinery, woodturning, pattern making, foundry work, forging and machine-shop. This gave him the background needed for a future in furniture design. Upon graduation, he worked as a cartoonist for the Bronx Home News from 1913-6. He was exempted from the draft for World War 1 because he was the sole provider for his mother and sister.

Rohde was employed by the Knickerbocker illustrating Service in 1917, working as a freelance commercial artist for Abraham and Straus, Macy's, W. & J. Sloane, and other stores and advertising agencies, developing a specialty in sketching furniture and interiors. In September 1922, Rohde enrolled in the Art Students League to increase his art skills. The league offered a wide selection of evening classes to accommodate artists, like Rohde, who worked full time. He went on to take eight classes at the League. To further his art education, he enrolled at the Grand Central School of Art around 1924. His job educated him on the different styles and designs of furniture while his classes introduced him to people active in the advertising world.

His job at Knickerbocker also

Rohde, Table Chromed Metal, Wood and Bakelite, 1928

put Rohde in contact with copywriter Gladys Vorsanger. She was instrumental in his career goal of designing furniture, encouraging him to go ahead with a trip to Europe he was contemplating in 1927. The result was a four-month voyage to Europe spent primarily in Paris and at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, during the spring and summer of 1927. While in Paris, he asked Gladys to come to Paris and marry him which she did after a required six week residency in September of 1927.

Upon returning to New York, Rohde began designing tables, desks, and other furnishings. "[H]is first 'design' studio consisted of one room in the newlyweds' East Thirty-third Street apartment, where he assembled his first tables from parts "outsourced" to various shops." (Phyllis Ross, Gilbert Rohde - Modern Design for Modern Living, 2009, p. 26) His early clients included small smoking tables used by Lord and Taylor as store fixtures and tables sold through a ship called Books 'n Things. His tables had chromed metal bases with tops of Black Lacquered Bakelite and stretched Fabrikoid (an artificial leather product made by the Du Pont Company). He leased an office in New York in 1929. He continued to make furniture with these materials well into the early 1930s, designs which were clearly inspired by his France and the Bauhaus visits.

Rohde gradually garnered more interest and clients. Three of his tables appeared in the Newark Museum's 1929 exhibition "Modern American Design in Metal" leading to an important commission which launched his career.

Norman Lee Apartment by Gilbert Rhode, Living Room Fireplace,

Greenwich Village, House Beautiful, November 1930, p. 485.

One of Rohde's earliest home interior design commissions was for the apartment penthouse for Wall Street broker Norman Lee, who had seen his display a the museum and wanted a design for his six hundred square foot Greenwich Village apartment. It consisted of a small entry hall, a relatively large living-room along with the necessary small bedroom, bath and kitchenette. Throughout his career, Rohde maintained an interest in creating multi-functional and modular furniture for small apartments and houses, perhaps stemming in part from this project.

An article written by Helen Sprackling for House Beautiful including copious photographs appeared in late 1930 giving Rohde's design a great deal of publicity. Rohde had created two small, open spaces in the living room - a corner 'office' with a desk and chair and a corner 'library' of a sort with a stepped 'Skyscraper' style bookshelf reminiscent of Paul Frankl. Sprackling explained that the living room was "a large capacious room with windows on three sides letting in adbundent light. We realize at once that this very light permits the general color scheme of gray, black, and red-orange, which in a less glowing room might be cold in spite of the vivid hue." (Sprackling, "An Apartment in the Twentieth-Century Manner", House Beautiful, November 1930, p. 486) Sprackling included several photographs detailing each space in the living room, giving visual confirmation of Rohde's style.

Rohde's Living Room Design for the Norman Lee's Greenwich Village Apartment, Photos From November 1930 House Beautiful:

Rohde's Living Room Design for the Norman Lee's Greenwich Village Apartment, Photos From November 1930 House Beautiful:[Top - Images from House Beautiful p. 484] Corner with Black Lacquered Chest; Fireplace with Couch Which Converts to a Bed 'and Rotorette' Rotating Shelf/Table;

[Bottom] Office Corner, with Harewood and Chromed Desk with Fabrikoid Cover, Chair and Light, House Beautiful p. 485; Study Corner with Floor Lamp, Chair and Black Lacquered 'Skyscraper' Bookshelf, House Beautiful p. 486; Radio Cabinet with Harewood Frame, Pottery Pheasant Sculpture, House Beautiful p. 486;

The publicity was good for Rohde's burgeoning career. At the behest of New York advertising agency Batton, Barton, Durstine and Osborn, their client Heywood Wakefield Lakefield Company hired him to design their first line of Modern furniture in 1930. His contract was for a large group of sunroom furniture, dubbed the Rohde Contemporary Group, the first part of which appeared at the Chicago market in January 1931.

Gilbert Rohde Dining Room Table, Maple with Bent Wood Supports,

Heywood Wakefield, 1930s, 1st Dibs

Some of this furniture was included in an exhibition of American Union of Decorative Artists and Craftsmen (AUDAC) members' work at the Brooklyn Museum. He continued designing for Heywood-Wakefield through 1933 and again in 1937, designing wood, wicker, reed, and rattan furniture as well as seats for schools and baby carriages.

The stock market crash of late 1929 resulted in a dramatically reduced demand for custom-made furniture causing designers to shift to designs which could be mass produced and sold more cheaply. Rohde followed this trend causing him to thrive in the early 1930s. Rohde began soliciting commissions in the Midwest in 1930, making contact with influential retail buyers from metropolitan areas. He received a thousand-dollar advance from the John Widdicomb Company in June of 1931 to design of a bedroom suite. This gave him the means to make another trip to Europe lasting two months. By the end of 1931 he relocated his office to a Modernist building "at the southeast comer of Lexington Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street, a change that augured well for the blossoming of his career during the coming year, with the addition of important new clients, commissions, and exhibitions." (Ross, p. 51)

Rohde Designs for Widdicomb and Heywood Wakefield, From Left: Dresser, Bird's Eye Maple, Black Lacquered Base, Bronze Hardware, Widdicomb, 1930s, Tropical Sun Rattan; Desk, Wood, Heywood-Wakefield, 1932, Worthpoint; Chair, Walnut Frame with Fabric Upholstery, Herman Wakefield, 1930s, Chairish

Rohde Designs for Widdicomb and Heywood Wakefield, From Left: Dresser, Bird's Eye Maple, Black Lacquered Base, Bronze Hardware, Widdicomb, 1930s, Tropical Sun Rattan; Desk, Wood, Heywood-Wakefield, 1932, Worthpoint; Chair, Walnut Frame with Fabric Upholstery, Herman Wakefield, 1930s, ChairishEarly in 1932, Rohde created a display for the 'Design for the Machine' exhibit of home furnishings and accessories at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. His 'A Man's Study' was furnished entirely with wood furniture from the Heywood-Wakefield Contemporary Group. It designed to represent an urban apartment showcasing the way his compact furniture was suited to small dwellings. At the same time, a line of children's furniture designed by Rohde was displayed at the New York headquarters of the Child Study Association of America (CSA). The Contemporary Juvenile Group had a Modernist aesthetic which embraced current ideas about early childhood development.

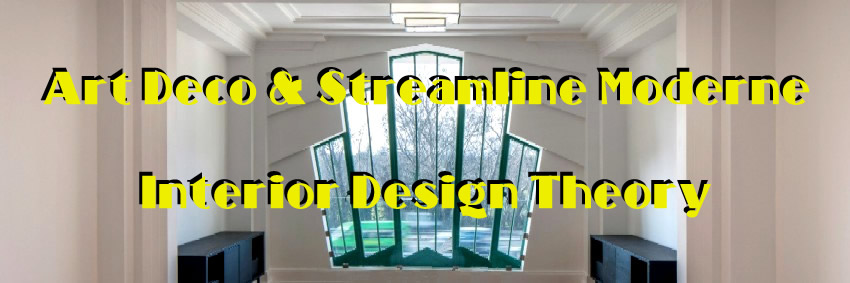

[Left] A Man's Study, Design for the Machine, 1932, Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum, Vol. 27, No. 147, Mar, 1932, p. 116;

[Left] A Man's Study, Design for the Machine, 1932, Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum, Vol. 27, No. 147, Mar, 1932, p. 116; [Right] Children's Nursery Design, Trimble Furniture, 1934, Period Paper.

Rohde first started talking with Herman Miller company president D.J. De Pree about the future of the furniture industry in 1930. De preparing furniture designs to show him. "Rohde argued that modern, middle-class lifestyles had changed, and required a new type of furniture. Smaller, more compact households could not accommodate large-scale pieces; fewer families employed servants to take care of the dusting

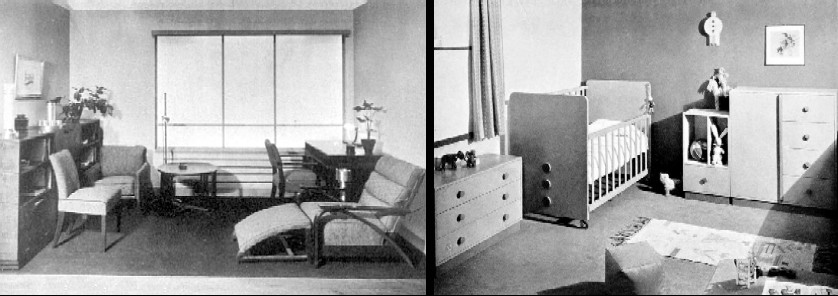

3305 Beds, American Walnut and Maple Burl, Herman Miller Trade Product Literature, 1933

and polishing that highly adorned furnishings required." (Gregory Cerio, "Gilbert Rohde: The man who saved Herman Miller", Antiques Magazine website, gathered 3-18-24) De Pree was feeling the pressure of the changing market along with a $30,000 loss, so he decided to look at Rohde's Modernist designs. He initially rejected them because they had almost no decoration, but Rohde refused to change them. De Pree reconsidered.

With losses mounting in 1931, Depree could not afford Rohde's requested $1000 fee (nearly 3 times what was normally charged). "Rohde instead proposed that he collect a 3 percent royalty on any furniture sold after it shipped. 'How could we lose on that?' De Pree later remarked. Born out of the hardship of the Great Depression, the royalty model devised by Rohde is one that persists in the furniture industry today." ("A model home for the modern era", Curbed website, gathered 3-18-24) Herman Miller began producing Rohde's bedroom suite 2185 in July of 1932, followed by a second bedroom suite, 3305, in November. The lines were 'conservatively modernist' wooden furniture with decorative veneers. Unlike other furniture lines which tended to remain in production for a couple years, the 2185 continued to be produced until 1936 and the 3305 line until 1939. This was to be he most important client.

Gilbert Rohde Furniture for Herman Miller 2185 and 3305 (From Left) - Valet, 3305 Series, Walnut and Burl Veneer, Brushed Chrome Handles, 1932, Invaluable; Dressing Table with Mirror, English Sycamore, Sucupiro and Plywood, 2185 Line, Herman Miller, 1932, Reddit; Dresser, English Sycamore, Sucupiro and Playwood, 2185 Line, Herman Miller, 1933-4, Wikipedia

Gilbert Rohde Furniture for Herman Miller 2185 and 3305 (From Left) - Valet, 3305 Series, Walnut and Burl Veneer, Brushed Chrome Handles, 1932, Invaluable; Dressing Table with Mirror, English Sycamore, Sucupiro and Plywood, 2185 Line, Herman Miller, 1932, Reddit; Dresser, English Sycamore, Sucupiro and Playwood, 2185 Line, Herman Miller, 1933-4, Wikipedia

Herman Miller was not his only client during the first half of the 1930s, however. Rohde created Modernist bedroom suites for three other companies in 1932-33: two for Widdicomb Company, one for the Tennessee Furniture Company, and one for Kent-Coffey. He was also commissioned by Thoneťs American branch to develop a line of upholstered seating around this time. He created a line of strikingly Modernist chrome furniture for Troy Sunshade in 1934. Troy Sunshade marketed the line under the banner " MADE BY TROY. DESIGNED BY ROHDE", a slogan which appeared in their promotional literature as well as one tags attached to the furniture itself.

Gilbert Rohde Furniture for Troy Sunshade Company, c. 1934

Gilbert Rohde Furniture for Troy Sunshade Company, c. 1934[Top] Setee, Model 46-40, Lacquered Chromed Steel, Blue Upholstery, Leather or Fabrikoid, Invaluable; Desk, Lacquered Wood, Pigmented Structural Glass and Chromed Metal, City Foundry; Club Chair, Blue Leather with White Piping, Chromed Metal, Jigidi

[Bottom] Rolling Bar Cart, Chrome, Stainless Tray, Pumpkin Lacquer, Incollect; Table, Chromed Metal with Lacquered Wood, Mid2Mod; Chair, Chromed Metal and Leather, The Swanky Abode

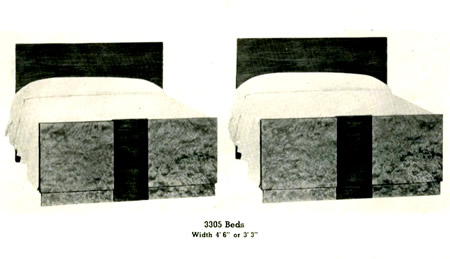

Rohde created another line of furniture for Kroheler Manufacturing in 1935 who wanted a line of budget modern and traditional furniture. The result was a 77 piece line created to appeal to bachelors, newlyweds and similar residents of small apartments and houses. Most of the pieces were solid wood and plywood, which saved costs on the veneer applications typical of his work with Herman Miller. "With Rohde's Smartset line, Kroehler joined the

Modular Cabinets, Wood, Ebonized, Rohde for Kroehler Furniture Smartset, 1935, Modernism

ranks of manufacturers producing modern furniture. The endorsement of Rohde's ideas by a mass marketer - whose products were sold at prices 20 to 40 percent lower than comparable Herman Miller products-helped advance his goal of furnishing every American home with modern designs." (Ross, p. 135)

In 1932, Rohde negotiated with Herman Miller and Heywood-Wakefield to jointly furnish one of the model houses at the Century of Progress World Fair in Chicago in 1933. The house eventually named the 'Design for Living' house after a play of the same name. Heywood-Wakefield immediately saw the promotional opportunity and agreed to furnish the open-plan living-dining-library space on the first floor. "The combined living room, dining area, and library created a feeling of spaciousness and provided maximum flexibility far entertaining and other social activities." (Ross, p. 81) De Pree was hesitant to commit Herman Miller, although Rohde eventually convinced him to supply two of Rohde's bedroom set designs upstairs.

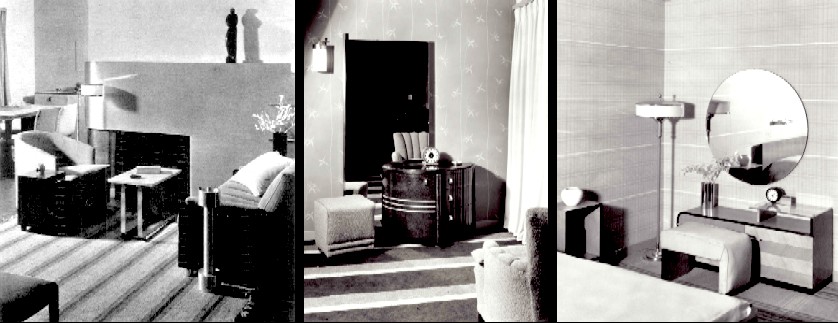

The Design for Living House, Century of Progress World Fair in Chicago, 1933 (From left): Living Room Heywood Wakefield Furniture, Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum, Smithsonian Institute; Master Bedroom, Furniture by Herman Miller, 3319 Ash Bedroom Group, Curbed; Second Bedroom, 3319 Ash Bedroom Group, Herman Miller, 1932, Curbed

The Design for Living House, Century of Progress World Fair in Chicago, 1933 (From left): Living Room Heywood Wakefield Furniture, Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum, Smithsonian Institute; Master Bedroom, Furniture by Herman Miller, 3319 Ash Bedroom Group, Curbed; Second Bedroom, 3319 Ash Bedroom Group, Herman Miller, 1932, Curbed

Herman Miller also supplied "seven radically modern clocks designed by Rohde in a variety of exotic woods, with accents of glass and chrome" for the Design for Living House. (Curbed) "The clocks became well known through publicity in magazines and newspapers-one article claimed Rohde's were the only modern clocks shown at the Century of Progress-and were distributed through department and specialty stores, including such New York retailers as Lord and Taylor, Altman's, and Ovington's, a popular gift shop." (Ross, p. 89)

Despite his initial reluctance, De Pree later recognized the Century of Progress exhibit altered his ideas about modern furniture after seeing the public reaction to the bedroom suites in the Design for Living House.

Some of Rohde's Clock Designs for Herman Miller: [Top] Cobalt Glass Clock, 1934 Machine Art Exhibit, Museum of Modern Art; Clock 4725B, Maidou Burl, Nickel Silver or Satin Chrome, Black Lacquered Base, 1933, 1st Dibs; Z Clock, Chromed Metal, Glass, Enamel, Century of Progress Brochure, 1934, Heritage Auctions

Some of Rohde's Clock Designs for Herman Miller: [Top] Cobalt Glass Clock, 1934 Machine Art Exhibit, Museum of Modern Art; Clock 4725B, Maidou Burl, Nickel Silver or Satin Chrome, Black Lacquered Base, 1933, 1st Dibs; Z Clock, Chromed Metal, Glass, Enamel, Century of Progress Brochure, 1934, Heritage Auctions[Bottom] Clock 4706B, Chromed Metal with Vertical Speed Lines, 1933, Incollect; Clock 4082B, Maidou Burl, Chromed Metal Speed Lines, 1933, Invaluable

1933 saw the introduction of Rohde's Laurel group of furniture, taking its name from the exotic wood used in the line. Some of the other groups introduced after Laurel included Mansonia (1935), Mahogany (1937) and Walnut (1939). "Laurel was

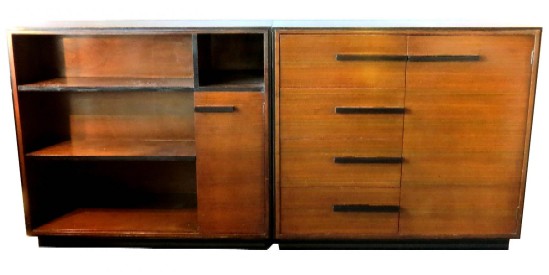

Rohde's Design for Herman Miller Chicago Showroom, 1939, Herman Miller

the first of eight coordinated lines Rohde developed for Herman Miller that featured unit, or modular, pieces. In addition, fifteen bedroom groups included chests designed for grouping. Out of a total of forty-five groups Rohde produced for Herman Miller between 1932 and 1944, nearly half incorporated the grouping principle." (Ross, p. 122)

In addition to creating such furniture lines in the latter half of the 1930s, Rohde became increasingly involved in the marketing and manufacturing of Herman Miller's furniture, designing four showrooms for the company including in Chicago, New York and Los Angeles. "It became clear that his [Rohde's] design innovations - the increasing emphasis on modular furniture and unusual combinations of materials, for example, as well as the concept of style stability-would require creative marketing strategies in manufacturers' catalogues and showrooms, in retail installations, and in sales training programs. More than any other American modernist furniture designer of his era, Rohde helped to create the marketing, publicity, and sales programs for his manufacturer clients, most notably at Herman Miller." (Ross, p. 99)

Cabinet Styles for Different Furniture Groups for Herman Miller by Gilbert Rohde (From left): East Indian Laurel and Nickel, Laurel Group, 1937, 1st Dibs; Model 3622 Cabinet, Walnut Veneer, Metal and Glass, Walnut Group, 1939, Stair Galleries; Secretary, Mansonia Veneer, Mansonia Line, 1935, Mutual Art

Cabinet Styles for Different Furniture Groups for Herman Miller by Gilbert Rohde (From left): East Indian Laurel and Nickel, Laurel Group, 1937, 1st Dibs; Model 3622 Cabinet, Walnut Veneer, Metal and Glass, Walnut Group, 1939, Stair Galleries; Secretary, Mansonia Veneer, Mansonia Line, 1935, Mutual Art

Around 1934, Rohde began designing lights for the Mutual-Sunset Lamp Manufacturing Company in Brooklyn. These included table and desk lights, floor lights and wall sconce fixtures. Not much is said about their relationship. One online sources suggests that Rohde designed more than 35 different lamps for the company in the 1930s. Unlike much of his furniture designs, the lamps don't appear to have been marked in any way to indicate that they were designed by him. Some advertisements link Rohde to Mutual-Sunset which is apparently the only way to be certain a Mutual-Sunset design is his.

Desk Lamps for Mutual-Sunset Lamp Manufacturing Company (From left): Copper Plated Shade, Chromed Base and Arm, Bakelite Plug, 1930s, Art Deco Collection; Chromed Brass and Enameled Aluminum, c. 1934, Wright Auctions; Black Enameled and Chromed Steel and Brass, Mahogany Base, c. 1935, Wright Auctions

Desk Lamps for Mutual-Sunset Lamp Manufacturing Company (From left): Copper Plated Shade, Chromed Base and Arm, Bakelite Plug, 1930s, Art Deco Collection; Chromed Brass and Enameled Aluminum, c. 1934, Wright Auctions; Black Enameled and Chromed Steel and Brass, Mahogany Base, c. 1935, Wright Auctions

As his presence at the Century of Progress exhibition suggests,

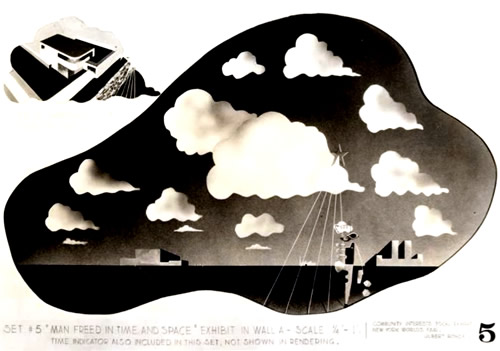

Rhode's Rendering for the Community Interests Focal Exhibit, "Man Freed in Time and

Space", 1939, NYPL Digital Collection

Rohde was an active participant in such exhibitions and similar events in the 1930s. These were an important way for interior designers to advertise their styles and companies. Ross notes that he participated in at least fifteen such events in the 1930s, including the New York World's Fair and the San Francisco Golden Gate Exposition, both held in 1939. His most ambitious event was the New York World's Fair. He was nominated to create a focal exhibit concerned with community interests at the entrance to the Town of Tomorrow display as well as being contracted by Anthracite Industries for an exhibit about the production of hard coal and by Rohm and Haas for a display concerning their new plastic products.

All these different projects he was working out necessitated the expansion of his design studio. "Until this point he had employed one or two draftsmen, a general assistant, and a secretary-receptionist, supplemented by freelance stylists and graphic artists as needed. To prepare the reports, presentations, models, and renderings required for fair exhibits, and continue work on existing accounts, Rohde hired eight new employees and rented extra space on East Fifty-seventh Street." (Ross, p. 168)

Like many other major figures in the Art Deco and Modernist movement, Rohde devoted some of his later career to teaching up and coming designers. His first foray into the field was with the New School for Social Research which hired him to teach a series of fifteen evening lectures called 'Modern Design in Home and Industrial Arts' in 1934. In 1935, he became the director of education for the Federal Arts Project's new school of industrial design called the Design Laboratory. As a WPA program, the school's mission was to train designers and teachers for free in an effort to provide employment for artists. He helped establish the program,

Biomorphic Coffee Table, Paldao, Acacia Burl and Leather Cloth, Paldeo Group, 1941, Bonham's

but had to resign from the position the following year due to overcommitment. He returned to teaching at New York University's School of Architecture and Applied Arts, serving as director of the industrial design program from 1939 through 1942. He also served as a visiting professor at the University of Washington (Seattle) around this time.

Rohde's company was also taking Herman Miller's furniture lines in a new direction in 1939 which was inspired by his third European trip taken in 1937 where his visited the for Exposition lnternationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (lnternational Exposition of Art and Technology in Modem Life). Eleven new lines of modern furniture were added to the Herman Miller catalog between 1940 and 1943. 1941 saw the introduction of the Paldao group of furniture Rhode at Herman Miller. This line of eighty mass produced pieces for living, dining and combination rooms embraced biomorphic designs based on natural phenomenon. Such designs prefigured the Midcentury Modern style which would become popular after Second World War ended. Unfortunately, all furniture production ceased in 1943 following a wartime ban on such products by the United States as the country focused on war production. Rohde did not see the ascent of the new Midcentury style, dying of a heart attack in 1944.

Sources Not Mentioned Above:

"Gilbert Rohde", Wikipedia, gathered 3-18-24

"Gilbert Rohde, FIDSA", Industrial Designers Society of America website, gathered 3-18-24

"Gilbert Rohde", Modernism website, gathered 3-18-24

"Gilbert Rohde and D.J. De Pree: The Partnership that Modernized the Herman Miller Furniture Company", The Henry Ford website, gathered 10-5-25

"Gilbert Rohde Collection, 1930-1944", Smithsonian Institute website, gathered 10-5-25

"Is my antique M.S.L.C. floor lamp designed by Gilbert Rohde?", Houzz website, gathered 10-10-25

Original Facebook Group Post

Related Facebook Group Posts: Rohde's Mutual-Sunset Lamps - Rohde's Small Spaces Furniture- Rohde Serving Carts - Rhode's Herman Miller Clocks - Norman Lee's Apartment - Rhode's Desks - Rhode's Troy Sunshade Furniture - New Rohde Biography