Lajos Kozma (1884-1948)

Lajos Kozma

Lajos Kozma (called Ludwig in German publications) was born in Kiskorpád, a small village in Somogy County, Hungary. He attended an elementary school in Marcali, Hungary, continuing his education in Kaposvár. After his father's death his mother remarried and the family moved to Győr where he completed high school at the Hungarian Royal High School. It was here that he became interested in the arts. In pursuit of this interest, he moved to Budapest in 1902 to attend the Royal József Academy of Fine Arts, finishing his studies in 1906.

Kozma became a member of the Society of Young Architects, an intellectual circle of young architects formed by Károly Kós to focus the creation of a modern, national architectural art which incorporated folk art and shepherd-carving motifs in their designs for buildings, churches, and gates. To facilitate this, they studied Hungarian folk art and local architecture by travelling in Somogy County and Transylvania. In their book on Kozma, Beke László and Varga Zsuzsa suggest that Kozma at this time saw architecture as a decorative art, connecting architecture and applied art. (See László & Zsuzsa, Kozma Lajos, 1968, p. 10)

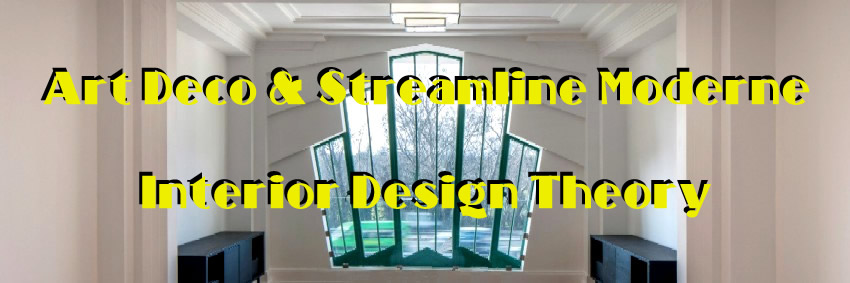

Kozma received a scholarship to study painting in Paris in 1909 where he studied under Henrie Matisse. Returning to Budapest in 1910, he joined Béla Lajta's design office. It was here that Kozma started to work in the applied arts. He designed Biedermeier interiors for the Rózsavölgyi House from Lajta's designs in 1912. He also designed the interior of Lajta's Rozsavolgyi bookstore, using glass panels to separate parts of the shop. Kozma, a skilled graphic designer, likely drew the decorative elements found in Lajita's architectural project such as the exterior decoration of the Erzsébetvárosi Bank on Vas Street. He created displays for KÉVE and designed the furnishings for New York Palace. Some of his illustrations and furniture designs were shown at the KÉVE (Magyar Képzőművészek és Iparművészek Egyesülete - Hungarian Association of Fine and Applied Artists) exhibition in 1911.

Building Designs for Béla Lajta - 1912 (From Left): Two Images of the Interior of Rózsavölgyi House, mkkvar; Decoration of Erzsébetvárosi Bank, Wiki

Building Designs for Béla Lajta - 1912 (From Left): Two Images of the Interior of Rózsavölgyi House, mkkvar; Decoration of Erzsébetvárosi Bank, Wiki

In 1913 Kozma left Lajta's studio and became a teacher at the School of Applied Art

Vitrine and Bench Seat, Hungarian Walnut, Budapest Werkstatte, 1914,

Innendekoration, August, 1914, p. 336

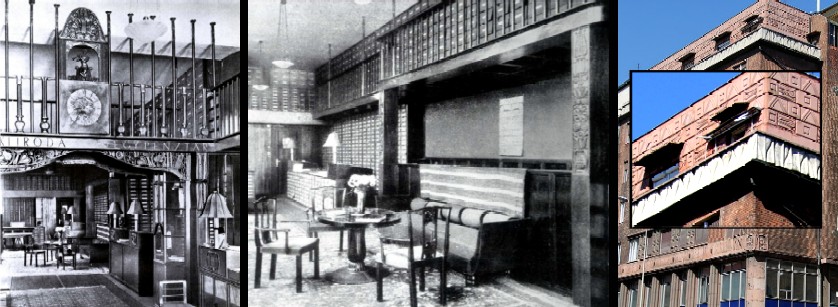

(Iparrajziskola tanára lett) in Budapest. He also founded his own Budapest Workshop that year, hoping to reform Hungarian interior design in a way similar the Wiener Werkstatte's reform f Viennese design. The Budapest Workshop focused on furniture making and home furnishings including lamps, mirrors and textiles with the intent to appeal to Budapest's rising middle class.

The Architectuul website suggests that he "was one of the most authentic representatives of Hungarian Art Nouveau in the early-20th-century." ("Lajos Kozma", Architectuul website, gathered 10-24-25) Yet, Kozma dismissed the style, explaining in the magazine Magyar Iparművészet (Hungarian Applied Arts) that Art Nouveau "subordinated the whole to [decoration, subjugating] the most important part ['(t)he structure, purposefulness, and materiality that define the works of applied art'] to the less important [ornamentation]." (Kozma, 'As Iparművészet Fejlődésének Új Trányáról", Magyar Iparművészet, Volume 18, Issue 8, 1913, p. 307) Still, as László and Zsuzsa point out, "in this period of his artistic activity, the features of the [Art Nouveau] trend he condemned can still be recognized" in his designs. (László and Zsuzsa, p. 12) Present also, as the images here indicate, were carvings of stylized folk art in his furniture.

Budapest Werkstatte Furniture, 1914, Innendekoration, August, 1914 (From Left): Desk and Chair, African Pearwood, p. 330; Large Chest in Hallway, Walnut with Rich Carving, p. 329 opp; Dressing Mirror with Drawers and Chair, p. 336

Budapest Werkstatte Furniture, 1914, Innendekoration, August, 1914 (From Left): Desk and Chair, African Pearwood, p. 330; Large Chest in Hallway, Walnut with Rich Carving, p. 329 opp; Dressing Mirror with Drawers and Chair, p. 336

Hungary was chaotic during the First World War, undergoing four different changes in government. During the war, Kozma was in Serbia in 1915, working in artillery. Yet his interest in art and architecture remained. He wrote an article for 'Magyar Iparművészet' from the Romanian front in 1917 suggesting that the "canals, dams, embankments, bridges, viaducts, tunnels, piers and lighthouses" needed "a new type of engineer-architect" who could "create in the forests of iron

Zsuzsa Carried by Doves, Zsuzsa Bergengóciában, 1921, Axio Art

bridges and reinforced concrete vaults, [who] will tame the unwieldy mass of stone and weave the subtleties of graceful lines into the winding valleys hidden among the mountains." (Lajos Kozma, "Mérnöki alkotások, monumentális emlékek", Magyar Iparművészet, 1917, p. 215-6) He suggested that such structures embrace the the total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk) concept rather than simply building such structures in the most straightforward way which "would ruin our good reputation that we were a very socially conscious people!" (Kozma, "Mérnöki alkotások...", p. 215)

Kozma did not abandon the graphic arts during the war. In 1917, he created a series of drawings for his daughter Zsuzsa for a fairytale. The images were eventually published in 1921 by Sacelláry Kiadás in an edition of 500 copies called Zsuzsa Bergengóciában: álompanoráma huszonkét képben elbeszéli Kozma Lajos huszonkét betüre versbeszedte Karinthy Frigyes (Susie in Fairyland: A panorama narrated in twenty-two images by Lajos Kozma, collected in twenty-two letters by Frigyes Karinthy). Near the end of the war in the summer of 1918, Kozma met publisher Imre Kner. Disillusioned by the industrial printing and bookmaking, Kner was looking to return to the elegance and fine printing style of 18th century. Kner and Kozma worked together to create a Neo-Baroque printing style for Kner's firm. Kner then hired woodcutters to reproduce the drawings created by Kozma. The resultc combined Baroque and contemporary elements. Kner used Kozma's design in his Classics and Monumentum Literarum series. The images in these publications were very much in the highly ornate Baroque style, something which would dominate his interior design during much of the 1920s.

Kozma's Graphic Arts Created in the late 1910s (From Left): Two Designs Sketched in 1917 and Published in 1921 in Zsuzsa Bergengóciában, Grofjardanhazy on Tumblr; Letter for Imre Kner, c. 1918, Type Design Information Page

Kozma's Graphic Arts Created in the late 1910s (From Left): Two Designs Sketched in 1917 and Published in 1921 in Zsuzsa Bergengóciában, Grofjardanhazy on Tumblr; Letter for Imre Kner, c. 1918, Type Design Information Page

During the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic which followed the war (March 21 - August 1, 1919) Kozma was a member of the Arts Directorate and was made a professor at the Department of Interior Design at the University of Technology. When the HSR fell, his new positions went with it.

Kozma decided to close the Budapest Workshop in 1919 because of financial difficulties and became an independent designer.

Cabinet, Ebonized Walnut, Made by Josef Krausz, Wolfsonian

Collection, 1923, Wikimedia

Kozma worked from home [throughout his life], and although he had an extremely large number of assignments and had to work very hard, he employed few people on a permanent basis. He always designed himself, and the one or two people working in his office could not solve the independent design tasks, he only entrusted them with working out the details and making drawings. They were mostly young people just starting out, but the few years they spent with Kozma provided them with such a solid foundation that it influenced their entire later careers and they all prevailed after the war. ("Architect in a deck chair and at a drawing table", Artmagazin Online, gathered 11-12-25)

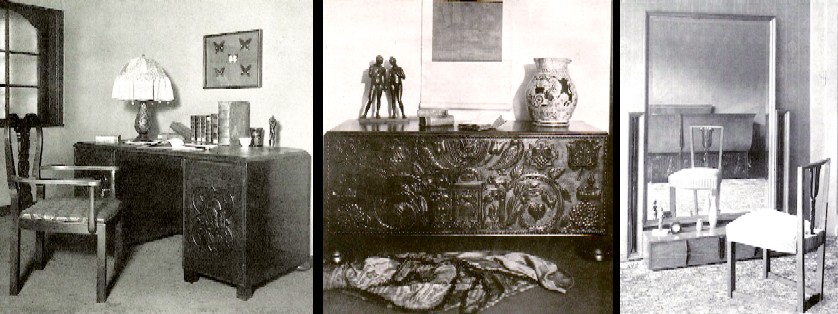

Although he designed some buildings during the early 1920s, he was primarily known for his furniture and interior designs during this period. Similar to his graphic arts, this furniture employed baroque elements, initially combining them with folk designs. László and Zsuzsa refer to his early furniture designs as 'folk-baroque'. It was produced by a variety of companies.

Kozma began to incorporate more contemporary elements during the mid and late 1920s in a style which became known as 'Kozma Baroque'. It was very popular, resulting in a large quantity of furniture being produced in the latter half of the 1920s. 'Kozma's takeoff on baroque-style furniture ...featured what today would be considered postmodern references to Hungarian folk art motifs, mixing luxurious traditional woods and materials in unexpected ways." ("Lajos Kozma", Architectuul) 'Kozma Baroque' used "intense colours or exaggerations of scale that served to emphasize the playful, witty elaboration of the historic motifs in a distinctively contemporary manner for the middle class consumer." (Paul Stirton, "Faces of Modernism after Trianon: Károly Kós, Lajos Kozma and Neo-Baroque Design in Interwar Hungary", Art East/Central, February 2021, p. 32) Because he was teaching in Budapest, some of his students employed the style which gained recognition outside of Hungary through Austrian and German magazines. His designs were awarded the Gold Medal of Applied Art in 1925 for his furniture.

Kozma-Baroque Furniture, Second Half of 1920s <Top> Vitrine, Wood and Glass, Pinterest; Side Table, Wood, Vintage; Carved Mirror, Gilt Wood and Mirror Glass, Bidsquare

Kozma-Baroque Furniture, Second Half of 1920s <Top> Vitrine, Wood and Glass, Pinterest; Side Table, Wood, Vintage; Carved Mirror, Gilt Wood and Mirror Glass, Bidsquare<Bottom> Dining Room Set, Wood, Uphostery, Selency; Bed, Gilt Wood, Magyar Kurir

During

Kner Villa, Gyomai, Hungary, 1925, Pinterest

During this period, he also created architectural exterior and interior designs. These included stores a pharmacy, a department store a movie theater, the Kassa Synagogue and some apartment buildings. Two of his residential buildings from the 1920s stand out: the Austerlitz Building in Budapest (1924), and the Kner Villa in Gyomaendrőd (1925). His houses were not considered as notable. "The independent buildings designed around 1925 do not yet show much of the later mature artist. These are usually single-storey villas; Baroque or classicist afterthoughts, with a flat mansard roof, strongly emphasized vertical openings, French windows opening onto a balcony, and elsewhere with facades reminiscent of folk baroque." (László and Zsuzsa, p. 17)

In the late 1920s, Kozma's style began to transform yet again, this time departing dramatically from the style of his previous work. "If an artist changes his style in a short period of time, the reason for this is often not to be found in his own internal development, but in some external influence. ... After more than two decades of Kozma's logically successive style periods — the Hungarian version of Art Nouveau, folk baroque, "Kozma-baroque" — there is now [1929-30] a turn towards a modern perception that eliminates both the formal characteristics and the theoretical foundations of his previous oeuvre." (László and Zsuzsa, p. 19)

Stefánia u. 63/c by Kozma, Wikimedia

In 1927, he built a residential building in what is considered Art Deco style at Stefánia u. 63/c. His designs began to increasingly reflect the clean lines of Modernism. Writing in the German Magazine Innendekoration in April, 1929, Kozma noted that styles in Hungary had moved through "representative remnants of historical housing design, then Art Nouveau, then the Romanticism of misunderstood folk art, then the decorative arts' barrage of ornamentation, then the asceticism of a ideologically driven Constructivism" (Kozma, p. . This was practically a description of his own progression.

Kozma now suggested that new houses should have "a more elemental relationship with nature leaves facades and walls open; no anti-nature tradition hinders the full flow of garden colors, floral scents, and sunshine. First light, air, nature—then architecture!" (Ludwig (Lajos) Kozma, "The Freer Spirit in the Home", Innendekoration, April, 1929, p. 151) Among his proposals for this style were "immediacy of expression, simplicity, and purity of gesture; simple clothing, unadorned furnishings, and functional, technically sound spaces", which required "new doors, new windows, airy bay windows, terraces, bold floor plans, flexible, asymmetrical arrangements of mass, often flat roofs, and, to emphasize integration with the landscape, strong horizontal articulation." (Kozma, p. 153) These concepts are heavily influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright's Organic Architecture, combined with some ideas from Modernism, or what he referred to as Functionalism. (He specifically mentions Wright as an influence in the article.)

An article written by Gyula Hay in another German magazine in 1930 discusses the transformation of his style during this time. "The ornamental, craft-based, and architectural style rooted in Hungarian folk art and drawing on Baroque reminiscences ['Kozma Baroque'], whose standard-bearer Ludwig Kozma was until recently, has lost its support in recent years: namely, Ludwig Kozma himself. ...his new work contains far fewer external elements than his old." (Hay, "The New Works of Ludwig Kozma", Moderne Bauformen, Volume 19, 1930, p. 163)

Armchairs, Couch, Table, Sleigh Bed, Nightstand, Exhibition at Kner Printing Museum,

Museum.hu. Commenters call this Kozma-Baroque, but there is a lot of the Modernist

influence seen here. (I would call it transition furniture.)

The article goes on to say that young Hungarians were "turning away from the old world and yearning for a new one—this youth felt less and less connection to the folksy, romantic forms of expression that drew on the legacy of a feudal society. In their eyes, these had become anachronisms." (Hay, p. 163) The rejection of excessive ornamentation by Modernist/Functionalist which followed the First World War was international in scope as designers and consumers both sought to break with tradition and with Art Nouveau. Hay's article suggests that Kozma's post-war style reflected the desire, which is not entirely accurate. 'Kozma Baroque' enjoyed its greatest popularity during the post-war 1920s.

Another international trend which is particularly seen in the late 1920s and 1930s was the move from hand-crafted Arts and Crafts furniture and designs to machine produced designs. As Hay explains, "Practical purpose and technology take center stage... While graphic passion occasionally still finds expression in simplified, purified ornamentation [this is found particularly in Art Deco designs during this time], Kozma's hand has nevertheless created... a world of forms based on functional design, logically derived from the production process." (Hay, p, 164) This was the so-called 'Machine Age' style which drew much from the Modernist mantra. Yet, while Kozma's designs drew from Functionalism, they were not industrially produced. Kozma worked with Heisler furniture to produce his new style of furniture. Hay notes that while Kozma's designs would be better to embrace industrial production, "[i]n Hungary, the industrialization of home furnishings, as is happening abroad, is not yet a reality. Small-scale crafts and traditional trades still prevail here, and accordingly, art forms must be shaped in a way that is detached from tradition, but without succumbing to mass production." (Hay, p. 164)

Modernist Furniture by Kozma <Top> Sitzmaschine, Armchair, Walnut, Fabric Upholstery, 1930, Artnet; Kozma, Pharmacy Interior, Moderne Bauformen, Volume 19, 1930, No. 4, p. 170; Lounge Chair and Ottoman, Lacquered Walnut, Silk and Brass, Studio Agram, 1920s, Invaluable

Modernist Furniture by Kozma <Top> Sitzmaschine, Armchair, Walnut, Fabric Upholstery, 1930, Artnet; Kozma, Pharmacy Interior, Moderne Bauformen, Volume 19, 1930, No. 4, p. 170; Lounge Chair and Ottoman, Lacquered Walnut, Silk and Brass, Studio Agram, 1920s, Invaluable<Bottom> Nightstands, Walnut Veneer, 1930s, Mallams; Desk and Chair, Walnut and Rosewood, Upholstery, 1930, Art Origo

The 1930s saw an increase

Atrium House Lobby, 1935, Modernism in Architecture

in the number of buildings designed by Kozma. These included several villas in the hills of Buda. "It was in these homes - where he designed both the structures as well as every element of the inside, from the floor coverings to the fixtures to the type of glass used in the windows - that he did some of his finest work." ("Lajos Kozma", Architectuul) The Hungarian Wikipedia entry notes that the houses and villas he designed were primarily in the second district of Budapest, having a "connection to the avant-garde (Bauhaus)." ("Kozma, Lazlos", Wikipedia Hungary, gathered 11-1-25)

Among the 'important' buildings he designed during this period were the Atrium House on Margaret krt. 55th (1935), the Glass House on Ü Vadász Street (1935) which has been greatly modified from his design and his one room holiday home on the island of Lupa. An extensive list of the dozens of buildings he designed between 1927 and 1940 can be found on the Hungarian Wikipedia entry. He did not design any public buildings during this period something which has been suggested to be due to his Jewish heritage. (See "Lajos Kozma", Architectuul)

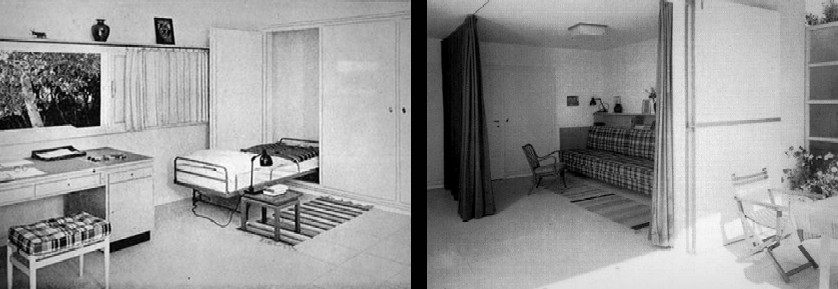

Kozma's Holiday Home in Lupa, Built 1932, Of Houses (From Left) Desk and Nurphy Bed; Living and Dining Areas

Kozma's Holiday Home in Lupa, Built 1932, Of Houses (From Left) Desk and Nurphy Bed; Living and Dining Areas

The Second World War was not kind to Kozma.

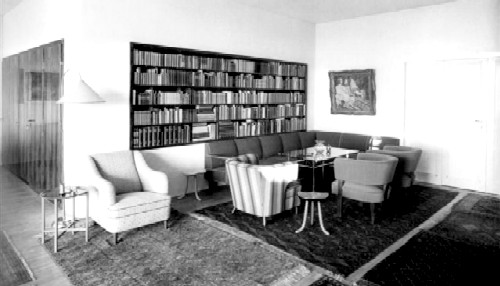

Living Room from Kozma's Book Das neue Haus, 1941, Darabanth Auction House

He lost his membership in the Chamber of Architects - essentially his license to work as an architect in Hungary - in 1938 because of anti-Jewish laws. "Kozma responded by writing a book of his architectural principles, illustrated by his work, 'The New House,' which was published in Switzerland in 1941." ("Lajos Kozma", Architectuul) Lazlo moved to a new apartment in Budapest in 1939 which was destroyed during the war. He then moved with a friend as well as spending time in the holiday home in Lupa. During the Jewish Holocost in Hungary (1941-45), Kozma and his family obtained false papers and hid to avoid persecution.

After the war, Lazlo was reinstated as an architect and was able to establish a new office. He received his first public commission for the Kilián György street elementary school (today Németh László High School) in 1947. He was appointed director of the School for Applied Arts on Kinizsi Street in 1946 and made a professor at the School of Architecture at Budapest Technical University. He joined the editorial board of a modernist architecture journal Uj Epiteszet (New Architecture) and became the leader of those who grouped around it.

Club Chair, Walnut and Leather with Brass Tacks, Newel

Sources Not Mentioned Above:

Attila Nizalowski, "A mi nyelvünkön, magyarul – Gondolatok Kozma Lajos 'metamorphosis Hungariae' életszemléletéről", Mandiner website, gathered 11-1-25

"Magyar Képzőművészek és Iparművészek Egyesülete", Hungarian Wikipedia, gathered 11-2-25

Paul Stirton, "Faces of Modernism after Trianon: Károly Kós, Lajos Kozma and Neo-Baroque Design in Interwar Hungary", Art East/Central, February 2021, gathered 11-2-25 (Line to Pdf File)

"Hungarian Soviet Republic", Wikipedia, gathered 11-5-25

"CLASSIC KOZMA - The Budapest Workshop and Lajos Kozma", Museum of Applied Arts Hungary website, gathered 11-5-25

"Der Freire Geist in der Wohnung", Innendekoration, April, 1929 pp.151-4

"Zsidó holokauszt Magyarországon", Wikipedia, gathered 11-9-25

Tome Teicholz, "Design with a "Z" (Lajos Kozma and Szalon)", Jewish Journal website, gathered 11-9-25

Amber Winick, "Lessons from Objects: Designing a Modern Hungarian Childhood 1890-1950.", Hungarian Cultural Studies, Volume 8 (2015), pp. 79-96

"Zsuzsa Bergengóciában : álompanoráma huszonkét képben elbeszéli Kozma Lajos huszonkét betüre versbeszedte Karinthy Frigyes", Abe Books website, gathered 11-11-25

"Architect in a deck chair and at a drawing table", Artmagazin Online, gathered 11-12-25

Modernist Chairs by Kozma (From Left): Arm Chair, Faux Leather and Wood, c. 1930, 1st Dibs; Deconstructed Arm Chairs, Walnut, Upholstery, Nickel-Plated Steel, Linoleum, 1932, Wright Auctions; Green Arm Chair, Wood, Paint, 1930s, Pamono

Modernist Chairs by Kozma (From Left): Arm Chair, Faux Leather and Wood, c. 1930, 1st Dibs; Deconstructed Arm Chairs, Walnut, Upholstery, Nickel-Plated Steel, Linoleum, 1932, Wright Auctions; Green Arm Chair, Wood, Paint, 1930s, Pamono