Virginia Hamill (1898 – 1980)

"We derive our knowledge from the past, and our inspiration from the future. The last tea service, the last chair, the last automobile, the last costume, the last building, have not yet been designed." (Excerpted from The Broadsheet, No. 1, Rhode Island School of Design, March, 1935)

Victoria Hamill Johnson ~1980, From the

TMA Announcement of the Hamill Fund

Virginia Hamill (1898 – 1980) was one of the first (if not the first) female industrial designers in the United States. Like many industrial designers, she was only partly responsible for many of the designs in which she was involved. Rather, as she put it, “My business was selling ideas. It was necessary for a woman to interpret to manufacturers what a woman would buy for her home if it were available.” (Pat Harris, “Don't Talk – Demonstrate”, Tucson Citizen, Oct 21, 1975, p. 8) Nevertheless, she participated in the ideas behind a great many products, a designer of many of them and was widely recognized as an expert on the American woman’s attitudes about interior design.

Upon the death of Virginia’s father in 1908 in Montreal, her mother took $600 in savings and whisked her off to Europe. Over the next seven years, she enrolled Virginia in schools there, giving the girl exposure to a French, Swiss and Italian education. She attended school in the winters and the pair traveled in the summers, remembering that they spent $30 a month on school, $30 on a hotel room and $10 for everything else for the first three years there. “It was probably her [mother’s] love of learning and determination to make it on her own that instilled in her daughter the qualities that made her, too, a pioneer in her chosen field.” (Harris, p. 8) When they returned to America in 1914, Virginia finished her education at Mt. Vernon boarding school in Washington D.C. She then moved to New York to attend New York School of Fine and Applied Art (now the Parsons School of Design), paying for her education using scholarships and by teaching while she was studying. She appears to have graduated in 1922.

After graduation, she taught interior decoration at the New York school as well as lecturing at the New York University School of Retailing and Historic Design for three years. In 1923, she was teaching a new course on the Fundamentals and Application of the Principles of Interior Decoration. She also taught a course on Period and Modern Design Styles which is likely why Lord & Taylor took an interest in her. Although she does not seem to have taught regular classes at colleges or schools after establishing her consulting practice, she continued to be a celebrated speaker at educational organizations and exhibitions on topics related to interior design throughout her life.

In 1925, Lord & Taylor began planning their "Seven Early American Rooms," an exhibition of furnished rooms showcasing American

Victoria Hamill's Office, Rug Profits Magazine, 1930, p. 6

interior design from the early 18th to mid-19th century. These rooms featured authentic, rustic, and formal furniture, highlighting colonial and Federal-style, and were inspired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s American Wing. They invited Hamill to stage the exhibit. The Upholsterer and Interior Decorator explained, “The success of the American antique department over which Miss Virginia Hamill presided at Lord & Taylor’s, has encouraged the firm to inaugurate perhaps the largest department of this sort in the United States, a department divided into an Italian, French and Spanish section…” (“Antiques at Lord & Taylor’s”, The Upholsterer and Interior Decorator, November 15, 1926, p. 121)

In 1926, perhaps because of the success of the Lord & Taylor exhibit, Hamill decided to open her own office, calling herself a ‘decorative art consultant’ with an eye towards giving advice to home furnishing manufacturers. She decided this in part because she found that many products being offered by manufacturers in America and abroad were not what she thought the market would want. “[S]he found herself saying repeatedly: ‘If these things were designed differently I would buy them – as they are not they would not sell.’” She believed that manufacturers needed design and consumer requirement advice before the produced products rather than after. By July of 1928, Vogue referred to her as “a well-known expert on modern decoration”. (Helen Appleton Read, “Twentieth-Century Decoration”, Vogue, July 1, 1928, p. 95)

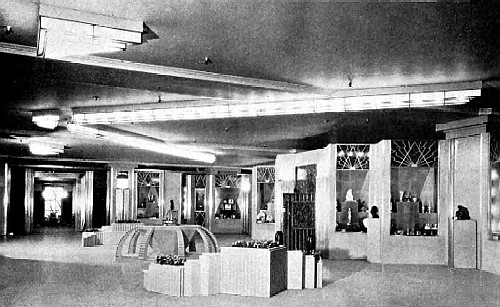

Macys International Exposition of Art and Industry, May 1928, Central Court of Honor,

Good Furniture Magazine, July 1928, p. 15

R. H. Macy hired her to consult on their upcoming 1927 exhibition 'Art in Trade' which was held in collaboration with The Metropolitan Museum of Art in an effort to showcase mass-produced modern decorative household goods and furniture. The next year, Hamill was again employed by the company for their international exhibition 'Art in Industry', co-directing the project with set director Lee Simonson. To populate the second exhibit, which was divided into the products of different countries, she visited ten countries in Europe over the course of two trips, returning with more than 5000 objects for the exhibition. Looking back at the two exhibits, she noted that Macy’s had had difficulty finding enough material for the 1927 exhibit. Following her trips abroad she explained that there was so much material for the second exhibit that they had to exclude some of what she had brought back. The second exhibition was considered the most ambitious department store project of its time. “I gathered up the material for the show,” says Mrs. [Victoria Hamill] Johnson, “and 250,000 people came to see it in two weeks.” (Harris, p. 8)

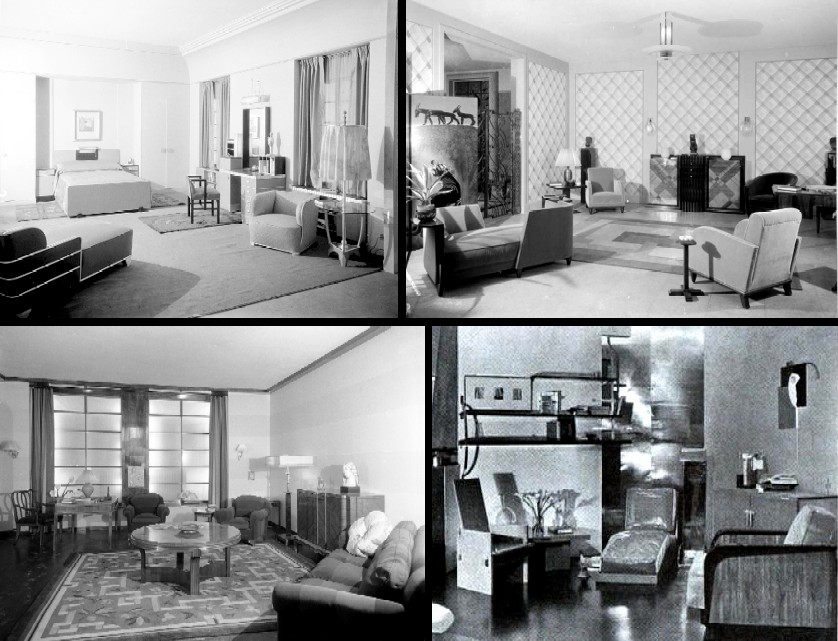

Rooms From Macy's International Exposition of Art and Industry, May, 1928: <Top> Combined Living and Bedroom, KEM Weber, 1928, Loc Gov; , Living Room with furniture by René Joubert et Philippe Petit, Loc.gov;

Rooms From Macy's International Exposition of Art and Industry, May, 1928: <Top> Combined Living and Bedroom, KEM Weber, 1928, Loc Gov; , Living Room with furniture by René Joubert et Philippe Petit, Loc.gov; <Bottom> Man's Study, Bruno Paul, 1928, Loc.gov; American Penthouse Studio by William Lescaze of New York, From Good Furniture Magazine, July 1928, p. 17

Hamill, Breakfast Set, Pewter and Ebonized Wood, Refinement of Jean G. Theobald's

Original Design for Wilcox Silverplate Co, c. 1928, Minneapolis Institute of Art

When dealing with companies, Hamill worked with only one account of a kind at a time, looking at all their offerings for home furnishings so that she could give advice on their product lines as they related to other lines.

In the late 1920s, International Silver Company’s Wilcox Silver Plate division brought her in to refine and modernize staff designer Jean George Theobald’s line of Dinette tea sets aimed at the modern woman. The sets each held a teapot, creamer and sugar, which fit together in clever and interesting ways on a tray for easy transport. Discussing the dinette set in Creative Art in 1928, Douglas Haskell said that it was “a fine example of what can be done…by an American commercial firm when it decides to appoint a modern designer of good judgment and sound taste.” (Cynthia Trope, “A Moderne Woman”, Cooper Hewett website, gathered 1-27-26)

Tea Sets for Wilcox Silverplate Co Made of Silverplate and Bakelite, With Jean G. Theobald, c. 1928: Diamet Set, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Breakfast Set, Minneapolis Institute of Art

Tea Sets for Wilcox Silverplate Co Made of Silverplate and Bakelite, With Jean G. Theobald, c. 1928: Diamet Set, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Breakfast Set, Minneapolis Institute of Art

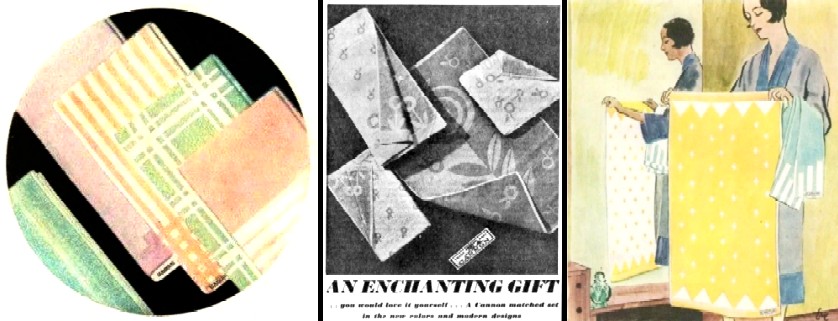

One of Hamill’s ideas was to create towels in different colors, something she felt would appeal to female buyers. She noted that 7 million bath towels were sold per week and they were all white. When she approached manufacturers with her idea to offer towels in different colors, they pointed out that such towels would cost three times as much. Cannon Mills decided to offer color towels in 1929. She further recommended that they package them stylishly leading to Cannon offering them with a matched set bathroom accessories in two and then in three colors, some with patterns. She also gave advice to retailers on how they should be displayed. The towels sold exceedingly well. As Paul Collins noted in an article on a special towel show put on by Cannon in 1931, “If there is a depression in textiles, Cannon Mills does not know it.” (Collins, “Towels Have a Show of Their Own”, The DuPont Magazine, November, 1931, np.)

Ads for Cannon Mills Colorful Towels: First and Third Images from Ladies' Home Journal, June, 1929, p. 20, Middle Image from Women's World, December, 1929, p. 20

In an interview, Hamill contrasted the attitude of the retail buyer and the female customer which helped explain the popularity of Cannon’s colorful towels. She noted that before buying, retail buyers typically ask the price, judge the quality by thread count and weight while barely looking at the product.

On the other hand the attention of the woman consumer is drawn to a product first because it appeals to her in design and colour if colour is involved. Second, she ascertains that the quality meets her demands (not being conscious that the linens are gauged by the number of threads to the square inch, or the blanket by weight) and finally, because the merchandise appeals to her, she asks the price. If she can afford it, she buys it, if she can't, she probably searches for something as close to it as possible within her budget. (Virginia Hamill, quoted in “Linen Guild's Style Consultant Talks Το Retail Heads”, The Linen Guildsman, March, 1931, p. 24)

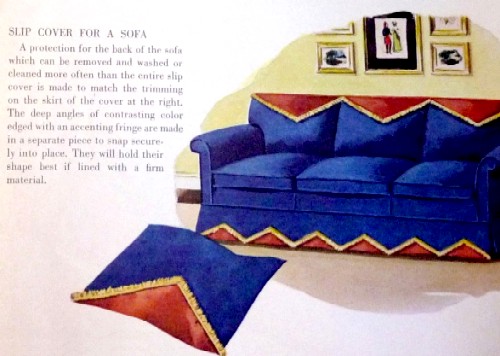

Sofa Slipcover Idea Image from Hamill's The Home Handicraft Book, 1941, Etsy

Hamill's name appears in several advertisements by companies for whom she worked in the 1930s. She was cited as an ‘internationally known authority on interior decoration (Columbus Coated Fabric Corporation. 1930), “the famous authority” on bedroom decoration and colors (Colorcovers, W. S. Libby Co., 1930) and “a leading stylist” (Collins & Aikman Carpet, 1930).

Hamill also wrote articles on home design for the magazine Women’s Home Companion between 1937 and 1942. Her topics focused on interior design and decorating for the home such as window drapery, antiques in décor, Christmas decorating, and appropriate furniture. She produced several pamphlets on interior decorating for women including The Important Points of Interior Decorating (1930), The Home Handicraft Book for Proctor and Gamble (1941) and A Woman’s Home Companion Booklet (1943).

Her talents also included scientifically based studies of how to market products to women. In 1930, the Bulletin of the International Management Institute explained that “one Woman, Miss Virginia Hamill, has made a life study of scientific forecasting of trends of textile styles, and so successful has this branch of specialism been that her clients – a group of America’s shrewdest manufacturers – reward her with £20,000 yearly. And they say she earns every cent of it.” (“D101 Scientific Forecasting of Successful Designs. – An American Woman’s Success”, Bulletin of the International Management Institute, July, 1930, p. 161)

Libbey Glass hired Hamill and Freda Diamond in 1942 to conduct a survey to discover what buyers would want once the Second World War ended. The pair visited more than 80 retailers and mail-order businesses in 25 cities, asking about customer views on pricing, packing, styling and merchandising.

Fernwood Dinner Plate for Edwin M. Knowles, 1940s

Shop in the Vintage Kitchen.

They noted “a movement toward a more casual, less fussy lifestyle. Women …wanted affordable, durable, and ‘livable’ glassware that could be used every day and for informal entertaining. ” (Linnea Seidling, “Women in Glasshouses: Communism in a Juice Glass – the designs of Freda Diamond“, Corning Museum of Glass blog, gathered 2-28-26) They recommended Libby design inexpensive, multi-use glasses which were mass produced and were readily available. Hamill doesn't appear to have any responsibility to Libbey beyond working with Diamond to conduct the survey and making recommendations about their product line.

During and after the Second World War, Hamill continued to consult and provide ideas, both for products and décor, to manufacturers and retailers. Much of the physical designs associated with her during this period involved patterns for fabric, wallpapers, and dishes. She created bedspread designs for the Lady Christina line of Bedspreads for J&C Bedspread Company in 1942, plate designs for Edward Knowles in the 1940s and 50s, suggested colors for telephones to Bell in 1956, advised Bates Manufacturing Company on bedspreads, designed wallpapers for Hextar, Devoe and Reynolds, C. W. Stockwell and Wall-Tex Companies, fabrics for The Palmer Brothers Company as well as drapes and displays for Celanese Corporation of America.

Hamill left New York in 1953 to open a studio and continue consulting with clients near Tucson, Arizona. She expressed interest in working on “ideas which have been simmering in my head for a long time, in new fields of endeavor.” (“Virginia Hamill Leaving New York for Southwest”, The Wallpaper Magazine, Vol. 38, 1953, p. 68) It is not clear when (or even if) she ceased to provide advice to industrial clients after this move. She became a patron of the Tucson Museum of Art. Upon her death in 1980.She gave the museum a bequest of $300,000 which outlined the creation of the

Quail and Foliage,Fabric and Wallpaper Sample Book, S. M. Haxtar Company,

c. 1950s

Virginia Hamill Johnson Fund and the Johnson Challenge, in which she stipulated that her gift be matched by museum members. This led to an expansion of the museum and continues to provide it with new works.

Hamill was very successful in her field. When she was hired by the Irish and Scottish Linen Damask Guild as their style advisor in 1930, a trade journal noted that she was “earning a larger salary than any other woman engaged in the linen industry.” (“The Woman Linen Expert”, Irish and Scottish Linen and Jute Trades Journal, June 18, 1930, p. 1) By May of 1930, a woman’s rights house organ reported that she – or at least her company - was making 20,000£ a year (an understated sum, apparently misquoted from the International Management Institute information) “and has extensive offices on the twelfth floor of one of Fifth Avenue’s newest skyscrapers. She employs a staff of eight women, including four designers and herself superintends their work.” (“How Women Work”, The Vote: The Organ of the Women’s Freedom League, May 2, 1930, p. 140) This shows the nature of her business at this time.

One final note: The surname ‘Johnson’ seems to have appeared after she moved to Arizona. From the ring on her hand seen in the photo of her at the top of this article, she was clearly married at that time. While no evidence of a marriage appears online, it seems to have occurred after she had established herself in practice as a designer. Italian artist Ugo Mochi made a silhouette of Virginia in 1939 which is identified with the surname Johnson which could suggest she married before that time, although it may just be the name given by the Tucson Museum, not by Mochi. Either way, changing a celebrated name so associated with her very successful consulting practice would have made little sense.

Silhouette of Virginia Hamill Johnson, Ugo Mochi,

1939, Tucson Museum of Art

Sources Not Mentioned Above:

"Virginia Hamill", Artera website, gathered 1-16-26

“Breakfast set, c. 1928”, Minneapolis Institute of Art, gathered 1-26-26

“World Art Exhibit Opened By Macy's”, New York Times, May 15, 1928, p. 8

“R. H. Macy & Co. Shows Modern Industrial Art”, The Carpet and Rug World, June, 1928, p. 21

Marilyn F. Friedman, Selling Good Design, 2003, p. 75-6 “The Little Schoolmaster’s Classroom”, Printer’s Ink, Sept 11, 1930, p. 152

G. A. Wahl, “Telephone Sets in Color”, Bell Laboratories Record, Vol. 34, July, 1956, pp. 251-4

USA Patent Office, Official Gazette of the US Patent Office, Feb. 18, 1930, p. 564

“New Celanese Showrooms Follow Modern Decorative Trends”, Draperies Annual, June, 1929, p. 80

“Press Preview: Far Eastern Walls”, C.W. Stockwell Co., Los Angeles, CA, Home Furnishings Calendar, March 17, 1949 -

Mary Roche, “Decorators Show New Home Designs“ New York Times, Mar. 22, 1949, p. 32

The Wallpaper Magazine, Volume 39, p. 164

“Current Topics of Trade Interest”, Good Furniture Magazine, October, 1923, p. 5

"Notable Faculty from NYSID's Past", New York School of Interior Design, p. 55, Retrieved from Issuu